Every nation lies to itself in the mirror of its own statistics.

In America’s case, that mirror is a spreadsheet — and lately it can’t even tell who’s who in the reflection.

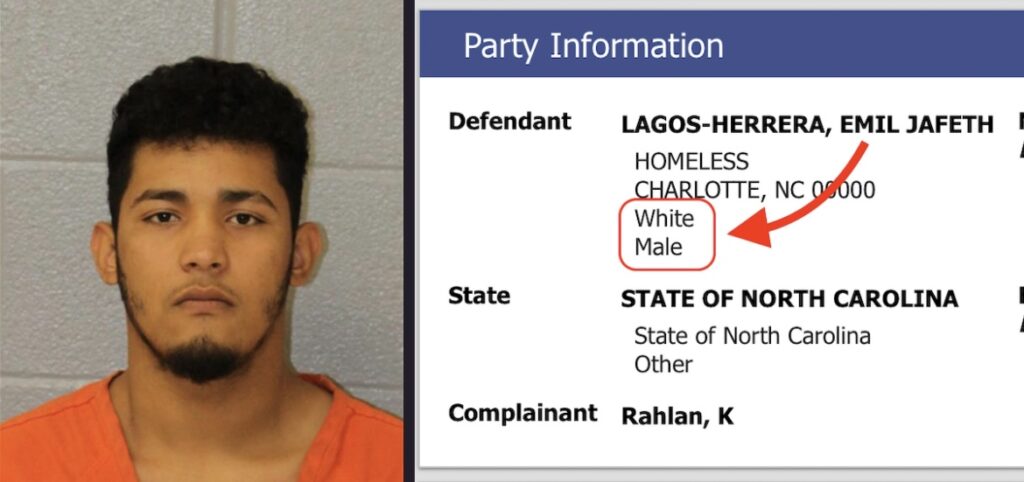

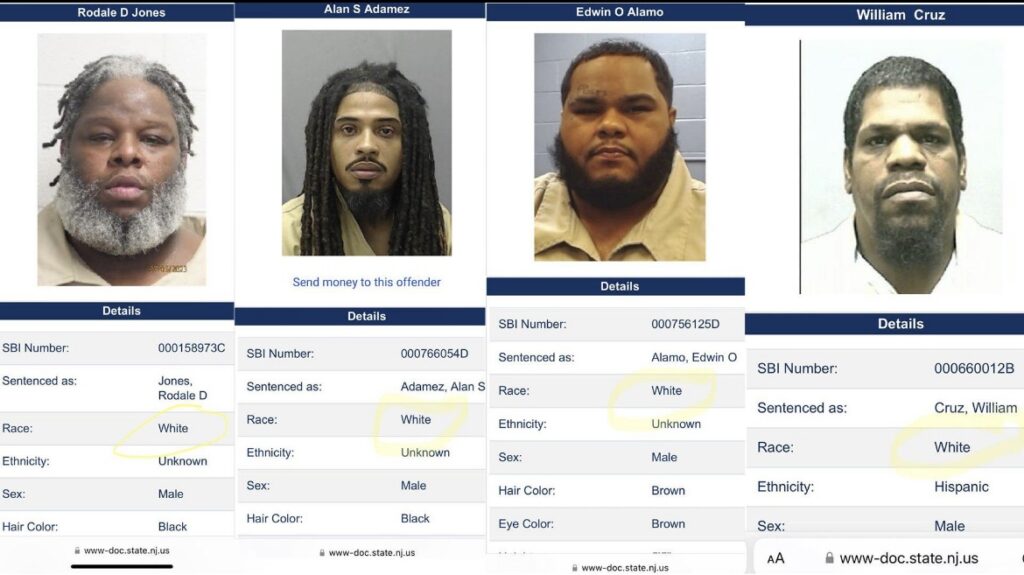

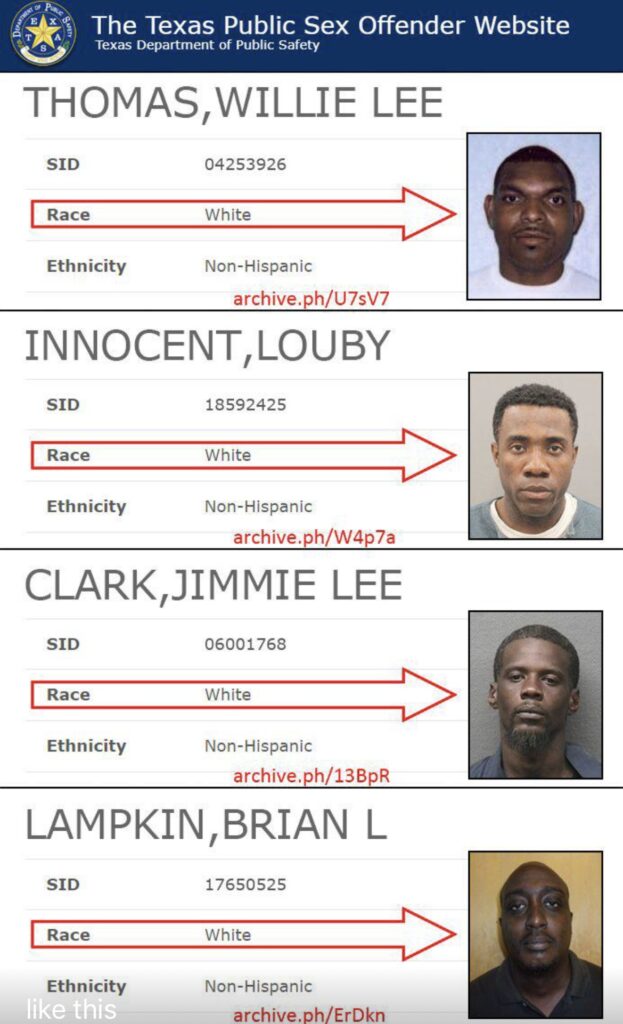

Across several states, official crime databases are quietly classifying Black and Hispanic defendants as “White.” A small but telling sample from public records in North Carolina and Texas shows the pattern: nine offenders, clearly identifiable as non-White, all recorded as “White” in state systems. It looks like a glitch until you realize it’s the result of an antique bureaucracy still using racial codes written in the 1970s — and never corrected for the demographics of a twenty-first-century country.

The Bureaucracy That Forgot to Update Its Drop-Down Menu

The root of the error isn’t malice; it’s maintenance. Most criminal-justice databases still rely on the Office of Management and Budget’s 1977 race-and-ethnicity standard: White, Black, Asian, American Indian, “Other.” The category “Hispanic” doesn’t exist as a race; it’s an ethnicity box attached later. Many systems simply default to “White” when the ethnicity field is blank.

In North Carolina, this happens because the statewide courts portal takes its data from arresting-agency submissions, many of which still use forms written for teletype input. In Texas, the offender registry uses a mix of self-reported and officer-observed race codes. If either field is missing, “White” becomes the system default. It’s the administrative equivalent of a shrug — a shrug that later becomes a statistic.

From Data Entry Error to Policy Reality

Once that record propagates through the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting and NCIC databases, it hardens into “national data.” Politicians cite it. Reporters quote it. Analysts build policy papers on top of it. The original miskey — a blank field, an unchecked box — becomes a data point in a congressional hearing about crime demographics.

This is how misinformation enters through the front door, wearing a badge.

It also explains why so many public arguments about crime and race feel unmoored from reality. Everyone assumes the data is neutral; no one checks how the sausage is digitized. The system doesn’t need to be biased; it only needs to be sloppy. Bureaucratic error produces the same distortions as prejudice — only cheaper.

Why the Numbers Lie

There are three overlapping failures here:

- Legacy architecture. Criminal-justice databases were designed for tabulation, not interpretation. They don’t adapt well to the social complexity of real people.

- Institutional incentives. Agencies have no reason to reconcile their data fields; accuracy doesn’t affect funding. Volume does.

- Narrative capture. Once “the numbers” exist, they acquire authority. Challenging them sounds like special pleading, even when they’re wrong.

The result is a feedback loop: flawed inputs → confident outputs → policies built on noise.

Colorblind by Design

The irony is that this isn’t a new discovery. Federal modernization memos going back to 2018 warned that the race-ethnicity standard was outdated. Pilot programs in a handful of states tried to introduce “multiracial” and “Hispanic White/Black” categories. The effort died in committee — too messy for the data analysts, too sensitive for the politicians.

So the system remained “colorblind” in the least enlightened sense: unable to see the very categories it insists on counting.

When Error Becomes Politics

Every debate that depends on demographic accuracy — sentencing disparities, policing bias, immigration trends — inherits this statistical rot. It isn’t that someone is cooking the books; the books were printed with missing pages. But try explaining that on cable news. It’s easier to fight about the meaning of the numbers than to admit they might be imaginary.

That’s why this small pattern from North Carolina and Texas matters. It isn’t about nine names on a spreadsheet. It’s a warning that our supposedly empirical understanding of race and crime is built on data that can’t pass a basic audit. America keeps arguing about the morality of a picture that may not even exist.

The Mirage Effect

Think of it as the “Statistical Mirage”: the numbers shimmer, appear solid, and vanish when you get close. Every policymaker who’s ever said “the data shows” should have to spend a week tracing where the data came from. Most would discover they’ve been debating the defaults of a 40-year-old database, not the character of a nation.

And yet, the mirage persists because it’s useful. A clean table of numbers feels safer than a messy conversation about human identity. Precision becomes a placebo.

The Fix That Isn’t

Technologists inside state justice departments know how to fix this. The problem isn’t software; it’s willpower. Updating the standards would force every linked system — from local arrest reports to federal dashboards — to recalibrate, re-audit, and, most dangerous of all, re-explain prior data. Admitting error at that scale would upend entire narratives. Bureaucracies don’t do confession; they do continuity.

So the misclassifications stay buried, producing a statistical version of “don’t ask, don’t tell.”

The Cost of Pretending to Know

The deeper issue isn’t who gets mislabeled; it’s that we’re comfortable basing billion-dollar policy arguments on data that no one actually validates. Accuracy is optional. Accountability is obsolete. The spreadsheet says “White,” and the discourse proceeds accordingly.

Until, of course, someone compares the mugshots.

Citations

- U.S. Office of Management and Budget – Race and Ethnic Standards for Federal Statistics, 1977

- Federal Bureau of Investigation – Uniform Crime Reporting Handbook, 2023 edition

- Texas Department of Public Safety – Criminal History Reporting Guide, 2024

- North Carolina Judicial Branch – Court Information System Overview, 2024