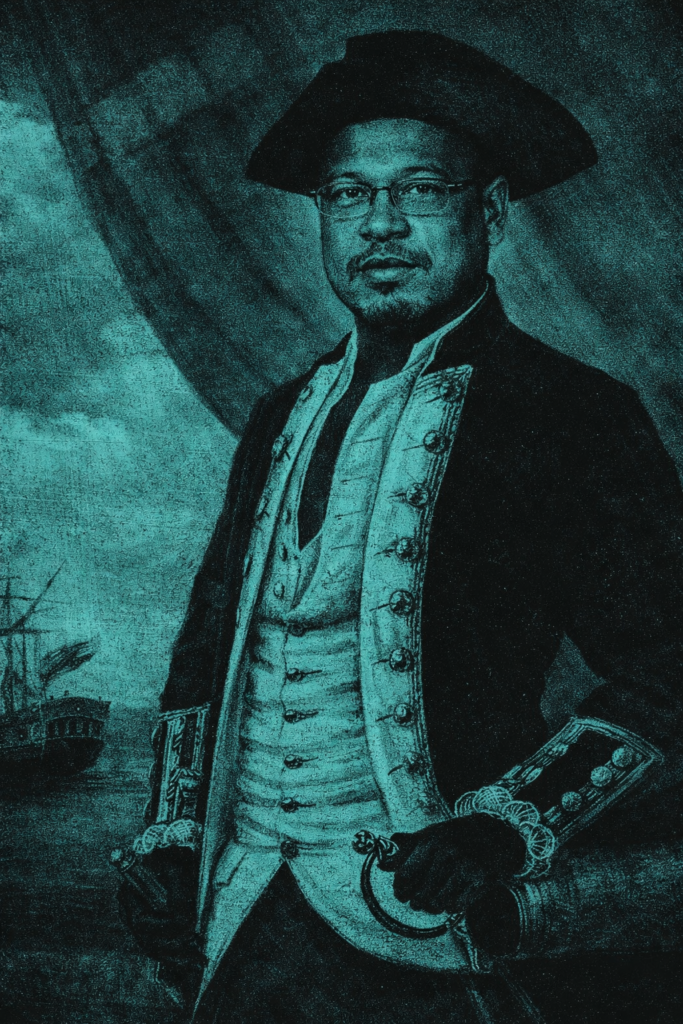

How Keith Ellison Became the Human Firewall Between Fraud and Accountability

Systems rarely fail at the edges. They fail at the interface.

In every large-scale extraction scheme—piracy, cartel finance, or modern nonprofit fraud—the decisive role is not played by the raiders or the recipients. It is played by the figure who stands between law and enforcement, who can slow, soften, or redirect scrutiny without ever formally stopping it. History calls this role many things. Today, we call it an interface.

Keith Ellison’s relevance to Minnesota’s cascading fraud scandals is not about proving intent or alleging a secret conspiracy. It is about identifying where power pooled, where warnings stalled, and where accountability became negotiable.

That is the real story.

What an Interface Does

An interface does not have to steal money. It does not have to falsify documents or direct subordinates to break the law. Its function is subtler and more consequential: to shape the environment in which enforcement decisions are made.

Interfaces prioritize coalition stability over disruption. They treat investigations as political variables rather than legal necessities. They understand that delay alone can be outcome-determinative, because systems built on urgency collapse when urgency is removed.

When an interface functions this way, wrongdoing does not need protection. It needs patience.

Ellison’s Office and the Minnesota Pattern

Minnesota’s fraud revelations did not emerge suddenly. They accumulated. State agencies flagged irregularities. Federal partners raised concerns. Internal warnings multiplied. Yet for years, enforcement lagged the scale of the problem.

During this period, Keith Ellison served as Minnesota’s Attorney General—the office charged with civil enforcement, consumer protection, and oversight coordination. Public reporting shows that his office had visibility into concerns well before the fraud reached its current scale. The question is not whether Ellison personally halted prosecutions, but whether his office acted with the urgency proportional to the risk.

Recent reporting has intensified scrutiny of that gap.

Recordings released by investigative outlets have raised serious questions about whether Ellison offered political considerations—campaign support, coalition relationships, or electoral calculations—as factors in enforcement posture. Even if one assumes benign intent, the appearance is corrosive. It signals to agencies downstream that enforcement is conditional.

In systems terms, that is enough.

The Cost of Conditional Enforcement

Once enforcement becomes conditional, every actor adjusts behavior accordingly. Agencies delay escalation. Nonprofits continue billing. Contractors assume tolerance. And recipients learn that oversight is performative rather than decisive.

This is how extraction scales without coordination.

The Minnesota cases reveal a familiar sequence: warnings issued, responsibility diffused, political risk assessed, action deferred. Each step is rational in isolation. Together, they produce systemic failure.

The interface does not cause the fraud. It enables the environment in which fraud becomes sustainable.

Coalition Politics as Shield

Ellison’s defenders argue that aggressive enforcement risked alienating key constituencies or feeding narratives of bias. That argument itself proves the problem.

When enforcement decisions are filtered through coalition management, law becomes contingent. That contingency does not protect communities; it exposes them. The victims of Minnesota’s fraud scandals were not abstract taxpayers. They were children, families, and legitimate service providers displaced by siphoned funds.

Coalition politics did not soften the damage. It magnified it.

Why This Matters Beyond Minnesota

Interfaces are exportable. The same logic that slowed accountability in Minnesota operates anywhere political identity is treated as a mitigating factor in enforcement decisions. It is the administrative cousin of selective prosecution—and it corrodes trust far faster than overt corruption.

History is blunt here: piracy collapsed only when ports were closed, not when raiders were scolded. Modern governance is no different. When interfaces protect systems instead of enforcing them, legitimacy erodes from the center outward.

Conclusion: Accountability Cannot Be Optional

This is not a call for ideological purges or punitive spectacle. It is a call for structural clarity.

Public officials cannot serve as both coalition managers and chief enforcers without creating conflicts that systems will exploit. When enforcement becomes negotiable, extraction becomes inevitable.

Minnesota’s lesson is not that fraud exists. It is that interfaces matter.

And when interfaces fail, nothing else works.

Citations

- American Experiment – “Feeding Our Future: Keith Ellison Caught on Tape” (2025)

- Department of Justice – Minnesota Pandemic Fraud Prosecutions (2022–2025)

- Minnesota Office of the Legislative Auditor – Grant Oversight Failures (2023)

- City Journal – “How Minnesota Became a Magnet for Fraud” (2023)

- Axios Twin Cities – DFL Internal Concerns Over Fraud Fallout (2025)

- GAO – Improper Payments and Oversight Risk (2024)

Pingback: Ports, Factors, and Prize Agents - #TCOT Reporter

Pingback: A Sanctuary for Disorder - #TCOT Reporter