For decades, Peru’s jumbo flying squid—pota—was a quiet economic miracle. The species migrates along the Humboldt Current in vast numbers, close enough to shore to sustain thousands of small boats, processing plants, dockworkers, and entire coastal towns. It was Peru’s second-largest fishery by volume, a protein engine that turned ocean abundance into wages and food security.

Then the industrial fleet arrived.

What followed was not a natural downturn, nor a mysterious ecological fluctuation, but a textbook collision between artisanal economies and state-subsidized industrial extraction—one that has now been documented across journalism, satellite data, and international fisheries analysis.

The Factory Fleet Model

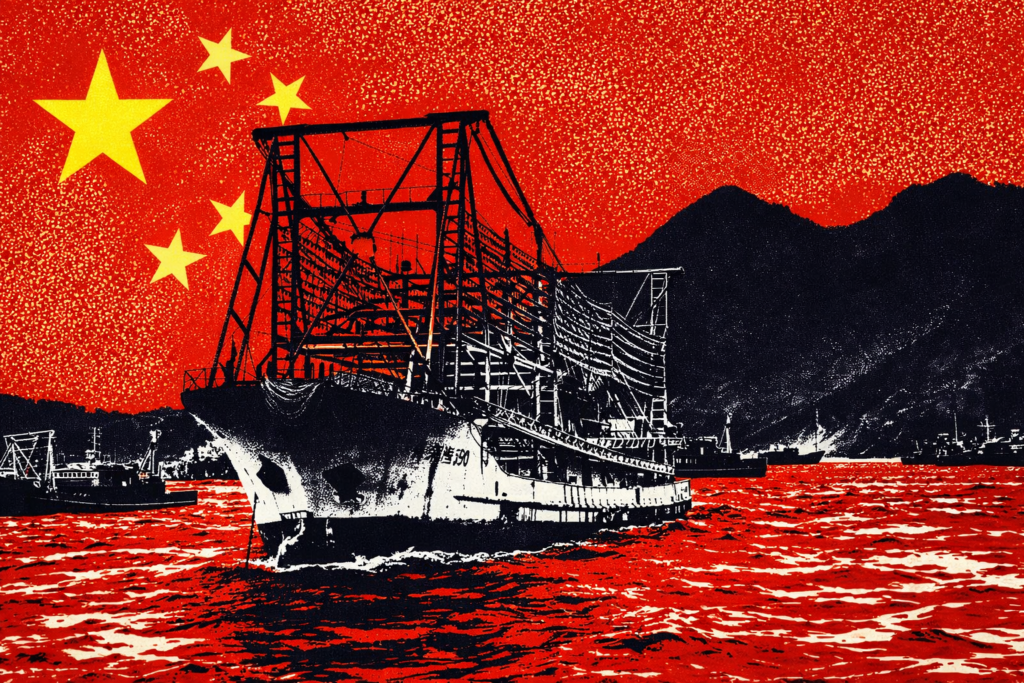

Reporting by Reuters traced how China built the world’s largest distant-water fishing armada, a fleet operating thousands of miles from home with heavy fuel subsidies, tax advantages, and political backing. Squid vessels—large, energy-intensive ships bristling with lights that draw cephalopods to the surface—became one of the fleet’s most aggressive components.

Unlike coastal fishing, this model is not seasonal or adaptive. It is continuous, mobile, and optimized for volume. When jumbo squid migrate along the South American coast, Chinese vessels do not wait at port or fish selectively. They follow the biomass in real time, forming dense lines just outside Peru’s exclusive economic zone, harvesting at an industrial scale that local fishers cannot match—or survive.

Fishing the Border Until the Fish Disappear

Satellite analysis from Global Fishing Watch shows the same pattern year after year: fleets massing along jurisdictional boundaries, tracking squid movement with precision. While technically operating in international waters, the biological reality ignores legal lines. Fish stocks collapse on both sides of the boundary.

This is where the abstraction of “international waters” becomes lethal. The squid do not recognize EEZs. When they are intercepted offshore in massive volumes, fewer make it to coastal zones. The result is felt immediately on land: smaller catches, longer trips, higher fuel costs, and ultimately boats that no longer leave harbor.

From Abundance to Absence

Environmental reporting by Mongabay documents the human fallout. Peruvian fishers interviewed describe once-reliable seasons turning into months of empty nets. Processing plants idle. Informal workers—often women—lose income first. Entire towns built around pota production hollow out.

The damage is not abstract or delayed. Jumbo squid are short-lived and highly sensitive to fishing pressure. When extraction exceeds regeneration, the collapse is swift. Assessments referenced by the Food and Agriculture Organization confirm declining sustainability indicators for squid stocks across the South Pacific, with overcapacity identified as a primary driver.

Scale as Strategy

What makes the Chinese fleet uniquely destructive is not simply overfishing, but scale paired with insulation from market discipline. The New York Times has documented how many of these vessels would be unprofitable without state support. Fuel subsidies, opaque ownership structures, and lax enforcement allow ships to operate at losses that would bankrupt independent fleets.

This transforms fishing from an economic activity into a geopolitical instrument. Local fishers must balance costs against revenue. Industrial fleets do not. They harvest until the marginal ecosystem collapses, then move on.

Marine advocacy groups like Oceana have warned that this model exports ecological damage while importing protein and profit back to China—externalizing environmental costs onto coastal states with limited enforcement capacity.

Devastation Without a Smoking Gun

The tragedy of Peru’s pota fishery is that no single illegal act needs to be proven for the damage to occur. The system itself does the work. Legal fishing at industrial scale, paired with biological reality and weak international governance, is enough.

By the time coastal communities demand relief, the squid are already gone.

This is not an isolated case. It is a preview. As global protein demand rises and near-shore fisheries are exhausted, distant-water fleets will continue to push outward. Wherever biology crosses borders faster than regulation, the outcome will look the same: abundance converted into extraction, livelihoods erased by efficiency.

Peru’s jumbo squid fishery did not fail. It was outcompeted by a factory model that treats oceans as inputs and coastal societies as collateral.

And once that model arrives, there is no natural recovery—only what remains after the lights move on.

Citations

- Nguyen Ho – Original Reporting

- Reuters – “Chinese fishing fleet’s hunt for squid devastates South American waters” (2020)

- The New York Times – “The Dark Fleet That Haunts the World’s Oceans” (2020)

- Mongabay – “How China’s fishing fleet is devastating squid stocks off South America” (2020)

- Global Fishing Watch – “China’s distant-water fishing fleet and squid operations in the South Pacific” (2020)

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) – South Pacific squid fisheries assessments (Various years)

- Oceana – Reports on distant-water fishing and squid fleets off Peru and Ecuador (Various years)